Doorstops and Doorsteps

MERRIE JOY WILLIAMS

(From Writing in Education, Issue No 73)

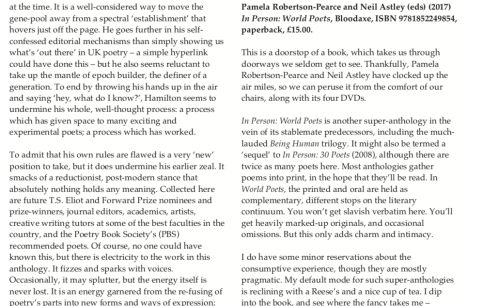

In Person: World Poets, ed. Pamela Robertson-Pearce and Neil Astley, Bloodaxe, £15.00, ISBN 9781852249854

This is a doorstop of a book, which take us through doorways we seldom get to see. Thankfully, Pamela Robertson-Pearce and Neil Astley have clocked up the air miles, so we can peruse it from the comfort of our chairs, along with its four DVDs.

In Person: World Poetsis another super-anthology in the vein of its stablemate predecessors, including the much-lauded Being Humantrilogy. It might also be termed a ‘sequel’ to In Person:30 Poets (2008), though there are twice as many poets here. Most anthologies gather poems into print, in the hope that they’ll be read. In World Poets, the printed and oral are held as complementary, different stops on the literary continuum. You won’t get slavish verbatim here. You’ll get heavily marked-up originals, and occasional omissions, but this only adds charm and intimacy.

I do have some minor reservations about the consumptive experience, though they are mostly pragmatic. My default mode for such ‘super-anthologies’ is reclining with a Reese’s and a nice cup of tea. I dip into the book, and see where the fancy takes me – usually to some great talent I’ve never heard of, or a poem I’ve returned to again and again. With pamphlets, I can sling one into my bag, and continue my adventures during lengthy bouts of travel. Sheer heft makes that impractical here, and my MacBook Air has finally found its limits – new models haven’t had DVD players for years.

That said, World Poetsis well-suited to the classroom, where DVD players are standard, and nowadays seen as a learning tool, rather than the tired teacher’s substitute. Printed foreign tongues, and newly-encountered alphabets, open for discussion such skirted-over matters as cultural context, the prior knowledge and value systems students bring to a poem, and a sort of horizontal linguistic drift which occurs in the act of translating across, rather than the temporal drift of individual languages. I once taught the poem, “First Ice” by the Russian poet, Andrei Voznesensky, alongside alternative translations called, “First Frost” and “The First Ice”, respectively. We explored the rich semantic territory, and with the insights gained most students surpassed prior attainment. But it feels naive to say now: we didn’t examine the poem in its original language.

What if we’d examined it in terms of shape or structure? What if students were encouraged to pool prior knowledge and work out their own provisional ‘translations’? This anthology makes such things possible, and by its sheer diversity is inclusive in a way terms like “Poems from Other Cultures” are not. Many students live ‘other’ cultures alongside their British one. Why not give EAL speakers the original in advanceof the lesson, a chance to step out from the margins to perhaps leadingfor a change?

Of course, these poems are worth enjoying entirely for themselves – but don’t take my word for it. A host of poets explore these subjects, and many others, far more eloquently. Arundhati Subranam, from Mumbai, whose powerful readings set her words on fire, writes, ‘You believe you know me,/ wide-eyed Eng Lit type/ from a sun-scalded colony,// reading my Keats – or is it yours – / whilst my country detonates/ on your television screen’. Ko Un, widely-known in his native Korea, attempts to bridge the gap. In “Time with Dead Poets” he tells us, “I am more than myself. You are more than yourself./ We sing in the universe’s dialect/”. Though their collections are shorter than some, both Jean Binta Breeze and Jack Mapanje add enriching cultural context on camera, in Breeze’s case about Jamaica’s recent history, in Mapanje’s, about his time in Malawi as political prisoner. His rendition of “Your Tears Still Burning at my Handcuffs, 1991” is even more moving for its poignant introduction.

Other memorable moments include Moniza Alvi’s “I Was Raised in a Glove Compartment”, which explores questions of love and belonging in a quite surreal way: “The gloves held out limp fingers” and “in the dark I touched them.” Ana Blandiana and her translator, Victoria Patea, give an impromptu joint reading, also to great effect. Not all of the poets are still with us. There is a moment, before Ruth Stone appears in the flesh, when we are faced with her empty chair and our own sense of loss. Finally, it’s always a delight to see Tony Hoagland, whose flair for plumbing the human psyche’s taboo depths can in equal measures delight and unsettle. But if World Poets is an expression of global connection, in these troubled times we need those poets who expose its undercurrents, a necessary act for healing. For like this anthology, all poetry is an attempt to move us through words, through worlds, to a universal space beyond linguistics. As the late Tomas Tranströmer attests in “The Half-Finished Heaven”, “Each man is a half-open door / leading to a room for everyone”.

Find out more about Writing in Education here.